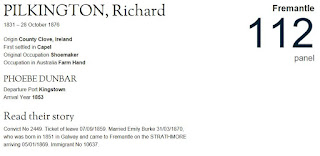

My grandmother Eve Pilkington (seated) presiding over

afternoon tea on the verandah of her home “Ennisvale”.

Pilkington Family Collection. 1908, digital image, personal collection.

While making a cup of tea in my household today involves simply tossing a teabag into a cup of boiling water, it wasn’t always like this. Ever since the 17th century when tea was introduced to the Western world by the Dutch East India Company, the ‘pot of tea’ has been integral to family meals and social occasions. For generations, people have celebrated life and shared troubles over a cup of tea. Whether it was a finely crafted silver vessel used for special occasions, a humble ceramic pot for everyday use, or even a tin billy over an outback campfire, the teapot and its contents was part of the ritual of daily life.

|

| Grandmother’s teapot, 2017, digital image, personal collection |

My oval-shaped teapot stands 14 cm tall. It is wider at the base, measuring 14.5cm x 12cm, and tapering to 12cm x 9cm across the top. The lid has a concealed hinge and an oval-shaped ivory finial on top. The sides are decorated with crossed branches of foliage, one with a butterfly and the other with a bird in flight. The lid is encircled by a wreath of foliage. The spout is fluted and tapers to a plain opening, with evidence of a soldered repair at the base. The hollow handle has a squared top incorporating a thumb rest for ease of pouring, and contains tiny holes at the top and bottom to dissipate heat. To minimise transition of heat, the handle is constructed with two expanders made of an unknown black material which I first thought was Bakelite. However, Bakelite was not invented until 1907, and I think my teapot is older than that. Some of the silver plating has worn off where the handle is gripped, and there is a small spot of corrosion on top of the handle. Two small dents and a superficial scratch on one side indicate that the teapot may have been dropped at some time.

|

| Grandmother’s teapot, top view, 2017, digital image, personal collection |

|

| Grandmother’s teapot, Base markings, 2017, digital image, personal collection |

The base of the teapot contains markings stamped into the metal. The first is what I initially thought to be the number ‘6’. In American silverware, this is a standard measurement for teapots, indicating a capacity of six half-pints = 1800ml. Besides the fact that my teapot is English, it only has a capacity of 1200ml so I knew this couldn’t be what the mark meant. On enlarging the photograph, it became evident that the mark was the number ‘5’, but as capacity this would equate to 1500ml; again not correct, unless it indicates capacity as five standard tea-cups. Another possibility is that as a mass-produced piece, this could be the journeyman’s mark, stamped on as a means of identifying how many pieces were made by a particular worker.

Foy & Gibson was a department store which first opened in Collingwood, Victoria in 1883. The Western Australian branch was opened in 1895 at 765 Hay St, Perth.

The number ‘2080’ is a pattern number, and was used to identify the design in sales catalogues. Pattern numbers were required to be registered, and would allow accurate dating of manufacture. I was unable to find any on-line listing of registered pattern numbers.

Made in England. The process of electroplating was first patented in England in 1840, and made silver tableware affordable for the growing middle classes. It involved applying a thin layer of silver over a base metal through the process of electrolysis. The industry became established around Birmingham and Sheffield in England, with numerous companies producing silver plated items that were usually marked with the letters EPNS (electro-plated nickel silver, plated onto a base alloy of copper, zinc and nickel) or EPBM (electro-plated Brittania metal, plated onto a base alloy of tin, antimony and copper). Each company stamped its products with its own registered maker’s mark.

My teapot contains no maker’s mark and is not stamped as EPNS. The wear on the handle and absence of hall marks makes me confident that it is silver plated. I suspect that it is probably the cheaper EPBM, due to the grey colour of the base metal showing through the worn handle. My conclusion is that it was a mass-produced piece made exclusively for Foy & Gibson by an unidentified manufacturer, in the late 1890’s or early 1900’s.

There is a picture of a similar style teapot in Foy & Gibson’s 1902 catalogue, advertised for 24 shillings. According to the Reserve Bank calculator, this would equate to $166.46 in today’s terms.

Victorian silver plated teapot. Source: Foy & Gibson 1902 Winter catalogue, University of Melbourne Library Digital Collections accessed 2 May 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/21263

I have speculated on how the teapot may have come into my grandmother’s possession. I know that she lived in Perth between 1901 and 1904, initially housekeeping for her brother and then after he married working as a housekeeper for others. Did she buy the teapot herself to add to her ‘glory box’ in anticipation of one day keeping her own house? Or perhaps it was a departure gift from a grateful employer when she returned to Victoria in 1904. Another possibility is that it was sent by her brother as a wedding gift when she married in 1907.

In terms of resale today, I don’t think the teapot has any monetary value. Similar Victorian teapots which include a maker’s mark are advertised on eBay for $30-$50. However, the value of the teapot to me lies in the connection it provides to the grandmother I never knew, who died only a few months before I was born.

This article was written in 2017 for assessment as part of the unit 'Place, Image, Object' in University of Tasmania's Diploma of Family History.