Just managing to get this National Family History Month post in before August is finished. This is an activity suggested by Alona Tester at: http://www.lonetester.com/2017/07/the-ancestral-places-geneameme/

Sounds like a fun activity to sort out which places are important to our family history!

Atherstone, Warwickshire, England – Elizabeth Arnold, my 4x g-grandmother was born here in 1788. She married Thomas Jennings in 1806. (maternal side)

Arctic Circle – William Frederick Pilkington, my 1st cousin x3 removed was lost and died here in about 1850. (paternal side)

For more see my blogpost Lost in Arctic Expedition.

Ardreigh, co. Kildare, Ireland – Alfred Haughton, my 2x g-grandfather, owned the mill on the River Barrow. (paternal side)

|

| Ardreigh Mill |

Brighton, Victoria, Australia – John Grant, my 3x g-grandfather, settled in Brighton in the 1840’s. The Grant family became significant property owners in the area. (maternal side)

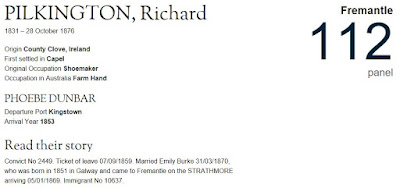

Clare, Ireland – home of my Pilkington family since at least the early 1700’s. Seven generations of Thomas Pilkington’s. (paternal side)

Cumberland, England – Abraham Postlethwaite (1831-1910), my 2x g-grandfather, was born and grew up in the village of Camerton before arriving in Australia in 1852. (maternal side)

Cork, Ireland – birthplace of Henrietta Osburne, my 2x g-grandmother. The Osburne family were a long line of medical men in Cork throughout the 18th, 19th & 20th centuries. (paternal side)

Dublin, Ireland – various family members have lived in Dublin over the last few centuries. Mt. Jerome cemetery is the resting place for several ancestors including my great-grandmother Mary Haughton Pilkington, and 2x great-grandmother Anna Keane Pilkington. (paternal side)

|

Pilkington grave at Mt. Jerome Cemetery, Dublin

|

Forres, Moray, Scotland – William McKerras, my 5x great-grandfather was born here in about 1753. (maternal side).

Greymouth, New Zealand – Charles David Gardner, my great-grandfather, was born in Greymouth in 1872. His mother Mary Emily Way had arrived there from Melbourne earlier that year. (maternal side). I have written about this at: Mary Emily Way

Hobart, Tasmania, Australia – Hobart was the beginning of a new life in Australia for several branches of my family. Grant (1827), Humphries (possibly 1820), Arpin (1832), Way (1852). None of them stayed in Tasmania, moving across Bass Strait to Melbourne, or across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand. (maternal side)

Inverness, Scotland – My 4th great-grandfather John McKerras (maternal side) was born in Inverness in about 1789. (maternal side).

India – My grandfather, Charles Osburne Pilkington (1866-1947), spent seven years in India from 1890 until 1897, serving with the 16th Lancers. I’d love to know what he actually did during that time, as there was no military conflict in that period. (paternal side).

Johannesburg, South Africa – My grandfather again. As a reservist in the 16th Lancers, he was called up to serve with the 12th Lancers for 3 years in the Boer War 1898-1902. Part of this time was spent serving in Johannesburg.

Kincardine, Perthshire, Scotland – The home of my Dewar ancestors. Great grand-father James Dewar was born in Kincardine in 1829. (paternal side).

Limerick, Ireland – 3x great-grandmother Margaret Bridget Moloney was born in Limerick in 1827. She left Ireland in the famine years for London, where she met and married Henry Way before migrating to Australia. (maternal side).

London, England – Birthplace of Louisa Jane Arpin, my 3x great grand-mother (maternal), as well as the mysterious Margaret Hill, my paternal great-grandmother about whom I have very little information.

Morankie, Ross & Cromarty, Scotland- Home of the McKenzie’s, where 4x great-grandmother Benjamina McKenzie was born in 1801, after the death of her father. A fact which prompted the priest at her baptism to note that she “was begat in the honourable bed”.

New Ross, Wexford, Ireland – the Elly family were Quakers and lived at New Ross, where they were merchants. Sarah Elly, my 3x great-grandmother was born here in 1761. (paternal side).

Oxfordshire, England – Henry Way, my 3x great-grandfather was from the village of Woodstock in Oxfordshire. (maternal side).

Port Phillip, Victoria, Australia – emigration destination for various family members. Most notably my 3x great-grandparents William & Louisa Humphries, who were among the first settlers to Port Phillip. They came across from Launceston on John Pascoe Faulkner’s ship ‘Enterprize’ in 1837. (maternal side). I've written Louisa's story in an earlier blogpost.

Queen’s County, Ireland – my 7x great-grandfather, John Pim, who was born in Leicestershire, England in 1641, moved to Ireland and settled in Queen’s county (county Laois). The Pim’s were Quaker merchants. (paternal side)

Raphoe, Donegal, Ireland – William Duffy, my 2x great-grandfather, and his wife Jane came from Raphoe before settling in Melbourne. (maternal side).

Somerset, England – 3x great-grandparents Thomas Tucker & Elizabeth Dunstone came from South Petherton in Somerset as assisted immigrants in 1848. (maternal side).

Shropshire, England – birthplace of William Humphries in 1796, 3x great-grandfather. He may or may not have been a convict. (maternal side).

Texas, U.S.A – my grandfather Charles Osburne Pilkington originally went to Texas in 1885. He spent about 4 years there before returning to Ireland and enlisting in the British Army.

United Kingdom – homeland of many of my ancestors, who at some point made the decision to emigrate to Australia.

Victoria, Australia – they came from all over Great Britain and Ireland, some via Tasmania & some via other places, but all ended up in Victoria at some point in their journeys. Earliest arrival 1837 and most recent arrival 1903.

Westmorland, England – Place of origin of my Quaker Haughton ancestors. Isaac Haughton, my 5x great grandfather, was born here in 1663. Sometime after his marriage in 1686, he moved to Ireland where he settled in King’s County (now county Offaly).

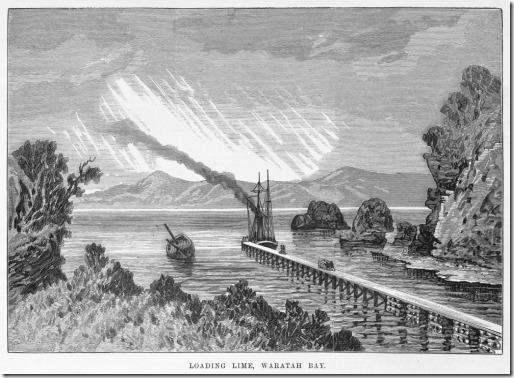

Walkerville, Victoria, Australia – Formerly known as the township of Waratah, Walkerville was settled in response to the establishment of the lime-burning industry. My grandmother grew up in Waratah, where her father James Dewar was manager of the lime kilns. I've written about the story of Walkerville here.

|

| Township of Walkerville & Kilns |

X - representing various forebears whose exact place of origin is unknown.

Yallourn, Victoria – my birthplace. The town of Yallourn no longer exists, it was demolished in the 1970’s to make way for expansion of the open cut brown coal mine.

Zzzzzz – that’s it from me for Family History Month!